Chicago Police officers have killed more people this year to date than the total number killed in 2010.

A quarterly report just released by the Independent Police Review Authority (IPRA) shows that 14 people were shot and killed by Chicago officers in the first six months of this year ending June 30. The Chicago Sun-Times reported Saturday that, according to news accounts that tally numbers through July 21, the number of fatalities is actually 16.

In 2010, 13 people were shot and killed by Chicago officers.

Chicago officials suggest that criminals are becoming more brazen than ever before. Critics suggest that Chicago police are feeding into a cycle of violence with aggressive policies.

Nationwide, it is a problem that has risen and fallen during the past decade, starting low at 180 in 2000 and peaking at 280 in 2006. In 2009, the latest data available, 238 felons were killed when attacking a police officer.

But it is important not to overinterpret "short-term changes to numbers that are relatively small,” says James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University in Boston. Chicago's claim that criminals are becoming more ruthless "is something you hear all the time.... It’s not new.”

For Chicago officials, however, it has been striking. The number of shootouts involving police this year is also nearing the 2010 total. As of July 21, the police were involved in 40 shootings. There were 46 shootouts recorded in 2010.

There is “a wanton disregard for the law,” says Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy. “People are willing to point and fire guns at police officers on a regular basis here in this city.”

But Chicago gang expert John Hagedorn suggests that the city's campaign against street gangs on the city’s West Side could be part of the problem.

Last August, in an unprecedented meeting, former Chicago Police Superintendent Jody Weis told area gang leaders that if one gang members shot another, authorities would trigger the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO), a federal law aimed at organized crime. Mr. Weis also promised a crackdown, resulting in increased parole visits and more traffic stops in their neighborhoods.

Then this June, current Superintendent McCarthy said his department would “obliterate” the Maniac Latin Disciples, the gang he held responsible for a shooting in Chicago’s Humboldt Park neighborhood that left two young girls wounded. “Every one of their locations has to get blown up until they cease to exist,” he told the Chicago Sun-Times.

But the confrontational approach is misguided because it only increases tension, often resulting in more shootouts with police, says Mr. Hagedorn, who teaches at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Many of the gangs are so deeply entrenched in Chicago – the Maniac Street Disciples date back to 1966, for instance – that attacking them will be ineffective, he adds.

“There’s a lot of ways to deal with gangs that have very deep roots besides war," says Hagedorn, who says the current approach “at this point is endangering their officers.”

Community-safety advocates agree that large police sweeps in certain areas increase the culture of violence on both sides.

“If you have the mindset that you need the military in the community, then people in that community feel under siege and everyone feels they’re going to get shot sooner or later,” says Tio Hardiman, director of Ceasefire Illinois, an advocacy group that works to diminish street violence.

A more-nuanced approach, he says, would involve the police educating young men in the community on how best to respond when stopped by police and by training police on how respectfully to approach local residents. Innocent people often become victims of violence because they don’t know how to behave when approached by the police, Mr. Hardiman says.

“Once you put all the guys in one category [of killers], everyone pays the price,” he says.

The IPRA conducts investigations of each shooting to determine if it is consistent with the police department’s official policy for use of deadly force, says Ilana Rosenzweig, director of the group. The findings can then help the department make changes, such as tweaking training procedures.

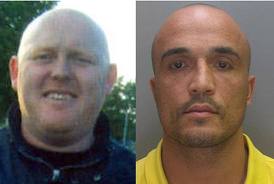

Police investigating a gangland double murder today recovered a second body from a burned-out van buried on a farm – and arrested another suspect in the case.

Police investigating a gangland double murder today recovered a second body from a burned-out van buried on a farm – and arrested another suspect in the case.

shooting in Lopez Mateos, in the city of Tepic, Nayarit. It was a clash between elements of the Police State and a group of armed men. The dangerous situation was roiled the streets Engineer Aguayo and Dolphin. A police element lost life in the shooting, authorities confirmed this Nayarit. The officer who died was identified as Gaston Santos desided Rangel. After the shooting there was intense in the area, so residents from the area claimed to have also indicated moments of horror suffered by heavy explosions.

shooting in Lopez Mateos, in the city of Tepic, Nayarit. It was a clash between elements of the Police State and a group of armed men. The dangerous situation was roiled the streets Engineer Aguayo and Dolphin. A police element lost life in the shooting, authorities confirmed this Nayarit. The officer who died was identified as Gaston Santos desided Rangel. After the shooting there was intense in the area, so residents from the area claimed to have also indicated moments of horror suffered by heavy explosions. in the town, the bloody outcome of the battle can be seen in the picture The gunmen burst the police building, were about 50 trucks of the Knights Templar , which generated an intense shootout and grenade attack. Reports said that the armed group tried to run to Miguel Angel Rosas and 30 elements of the Federal Police who were sleeping in the police building. It was almost an hour of confrontation, it alerted the public and that the intense blasts were unmistakable. On the site were over five thousand rounds of ammunition casings. The place was practically destroyed.In the action three gunmen were killed, they were identified as Cortez Fabian Rios, 23; Epigmenio Infante Hernandez, 30, and Pedro Cortez Ramirez 18. In addition seven elements of the Federal Police also lost their lives and three others were wounded. That event was the one that triggered the wave of clashes that occurred a few days in several municipalities in Michoacan, the area has become a war zone.

in the town, the bloody outcome of the battle can be seen in the picture The gunmen burst the police building, were about 50 trucks of the Knights Templar , which generated an intense shootout and grenade attack. Reports said that the armed group tried to run to Miguel Angel Rosas and 30 elements of the Federal Police who were sleeping in the police building. It was almost an hour of confrontation, it alerted the public and that the intense blasts were unmistakable. On the site were over five thousand rounds of ammunition casings. The place was practically destroyed.In the action three gunmen were killed, they were identified as Cortez Fabian Rios, 23; Epigmenio Infante Hernandez, 30, and Pedro Cortez Ramirez 18. In addition seven elements of the Federal Police also lost their lives and three others were wounded. That event was the one that triggered the wave of clashes that occurred a few days in several municipalities in Michoacan, the area has become a war zone.